A biography of Master T. T. Liang

TungTsai Liang (1900 – 2001) was a well known Tai Chi Master and author.

“On the twenty-third day of the first moon in the year 1900, Liang Tung Tsai was born in Ningpo, Hopei Province, which is a small town on the shores of the Yellow Sea in eastern China. Master Liang lived to the venerable age of 102, passing away on August 17, 2002.His father was a merchant, selling primarily sundries, and according to Liang was an extremely hard worker and devoted father. His mother was a devout lay Buddhist, who spent all her free time lecturing on Buddhism to children and helping monks acquire funds to build temples. Liang was born Jui Fu, and stylized his name when reaching adulthood as Tung Tsai. He had an older sister (deceased) and a younger brother, Jen Tieh, who is still living in California.

Liang spent four years studying at Nankai University in Tienjin, where he received an M.A. in economics and then entered the British Maritime Customs Service at the age of 24. His rank increased quickly, and by the time he was 35 he held the highest position of any Chinese officer. Only one British officer was higher in rank than him. During his initial years with customs he spent a great deal of time in Amoy, which he remembers as being ideal in comparison to Shanghai, where he was sent after his promotion to the rank of Chief Tide Surveyor.

Tung Tsai Liang (T T Liang) served in many of the major cities along the eastern seaboard of China. When he was promoted to the rank of Chief Tide Surveyor he was in charge of all British controlled ports within their concession along China’s eastern seacoast, an enormous duty.

In 1945, Liang fell seriously ill and was hospitalized for over fifty days in a Shanghai hospital. Suffering from pneumonia, liver infection, and severe gonorrhea, acquired from years of drug, alcohol, and sexual abuse, his doctors had given him approximately two months to live. In order to save his life he took up the practice of T’ai Chi and within six months had made great strides toward restoring his health. After he was fully recovered, he requested a transfer from the customs service, realizing that all his health problems were created from his wealth and position. In 1948, he was sent to Taiwan, which he saw as a disgrace, but later considered a blessing because Mao’s communist regime overtook China a couple of years later and he would certainly have been executed or imprisoned had he remained there. He found out later that he was on a list of persons to be executed. Unfortunately, his eldest son and daughter were still in China at the time and the communists had imprisoned, tortured, and interrogated them in order to locate Mr. Liang, events for which he was always extremely regretful. Mao had moved into northern China so quickly that all his efforts to retrieve them had failed.

Liang married twice, and his first marriage was arranged in 1928, but she died not long after his youngest son was born in 1933. She bore him three children—first son, Teh Yin, born in 1929; second daughter, Teh Chin, born in 1930; and third son, Jen Yin (Joseph), born in 1933. He married his second wife in 1943 in Tientsin (Hopei province). They had one daughter together, An Li, who was born in 1952. Mrs. Liang died in Los Angeles in 1993.

All his children are alive and well. His eldest son lives in Beijing, his eldest daughter in Tientsin, his youngest son in Tampa, Florida, and his youngest daughter is presently living in Los Angeles.

Liang moved from mainland China in 1948 to Taipei, Taiwan, and then to the United States in 1962. For six years he served as translator for Prof. Cheng Man Ch’ing (his primary T’ai Chi teacher) at the United Nations in New York. Since that time he had lived and taught in various places throughout the United States, such as Boston; St. Cloud, Minnesota; Tampa; Los Angeles; and finally New Jersey. He has also taught T’ai Chi at such prestigious universities as Tufts, MIT, Harvard, Smith, and Amherst. While living in St. Cloud, he and I taught at St John’s University and its sister school St. Benedict’s.

While serving in the customs service in Shanghai, Liang took up serious study of ballroom dancing, becoming a famous and champion dancer there. His expertise in dancing later affected his approach to T’ai Chi, as he felt that performing T’ai Chi to music provided the same relaxation that dancing did. His system of dissecting T’ai Chi postures into beats provided a very consistent and rhythmic manner in which to perform T’ai Chi.

All his forms soon had the name “dance” attached to them. Interestingly, his inclusion of dance and music has had a profound effect on all present day T’ai Chi practicers, as many have incorporated music into their forms.

Liang studied martial art and T’ai Chi with more than fifteen teachers. He was fortunate to have been in Taiwan in the 1950s because it was like a golden era for the internal arts, as many of the great teachers from China managed to escape to Taiwan during Mao’s takeover. Liang was wealthy and he maintained a very high position within the Republic of China government of Chiang Kai Shek. His wealth afforded him the ability to have so many teachers, and because his rank was so high teachers sought him out, as it would be considered a boost to both their career and school to have him as a member.

Throughout his career, Liang had appeared on numerous television and radio shows and been featured in many magazine and newspaper articles. In Minnesota in 1985 he was voted as one of five senior citizens who contributed in excellence to the betterment of youth. All five were honored with a week-long celebration at the Minnesota Science Museum in St. Paul, Minnesota. He also became a citizen of the United States in 1985.

Newspaper articles in China proclaimed him as one of the great living testaments to T’ai Chi practice.

Without question Liang became one of just a handful of men to achieve world recognition for his T’ai Chi skills and knowledge. He truly was one of the last great living masters coming out of the internal arts golden era of Taiwan. If anyone ever deserved the title Grand Master, it would have been him, as he not only acquired great skill but outlived all of his teachers.

Liang was the author of T’ai Chi for Health and Self-Defense (Vintage Press, 1974), which is one of the most popular T’ai Chi books in English.

His book and T’ai Chi—The Supreme Ultimate Exercise for Health, Sport, and Self-Defense by Cheng Man Ch’ing and Robert W. Smith (Tuttle, 1967) have

become standard authoritative works in English on T’ai Chi. Liang not only worked as the translator for Cheng’s book, but he also appeared in the Pushing-Hands section.

Master Liangs Martial Arts lineage

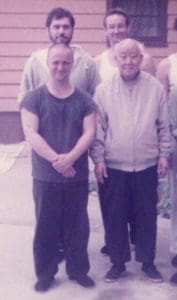

Ben Lo, T.T. Liang, Cheng Man Ching, Yi Ching Bo, Hsu Fun Yuen

Master Liang actually started his martial art career in high school in Tientsin. Between the ages of fifteen and sixteen his high school physical education teacher was the famous kung fu teacher Huang Han Hsun, who was a master of Praying Mantis Boxing (T’ang Lang Ch’uan).

In 1933, while undergoing a seminar for his customs training in Beijing, he studied Tui-Shou (Pushing-Hands) with Yang Cheng Fu, but was only able to do so for a couple of weeks and therefore never listed him as one of his teachers.

After his illness in Shanghai in 1946, he began studying T’ai Chi Ch’uan with various students of Cheng Man Ch’ing, and began formal training with Cheng in 1947. In 1949 in Taipei, Liang became Cheng’s Ta Shih Hsiung (Number One Chief Disciple).

From 1950 on, Liang began studying with as many good teachers as he could find. The names of some of these teachers, as well as what he primarily studied with them, are listed below. For those readers who may not be familiar with the contemporary history of T’ai Chi and what was surely the golden age of the internal martial arts in Taiwan during the 1950s, Liang’s resume of teachers reads like a Who’s Who of T’ai C

Prof. Cheng Man Ch’ing: (Disciple of Yang Cheng Fu): form and pushing-hands.

Li Shou Chen (Disciple of Yang Shao Hou): form and pushing-hands.

Chang Ch’ing Ling (Disciple of Yang Pan Hou): form and pushing-hands.

Hsiung Yang Ho (Disciple of Yang Shao Hou): form, pushing-hands, san-shou, meditation, sword, and sword fencing.

Wang Yen Nien (Disciple of Chang Ch’ing Ling): pushing-hands.

Chen Pan Ling: qigong and pushing-hands.

Huang “The Florist” (Disciple of Yang Cheng Fu): pushing-hands and long form.

Huang Han Hsun: Praying Mantis Kung Fu

Wei Hsiao Tang: Praying Mantis Kung Fu

Taoist Yang (Disciple of Yang Lu Chan): meditation, pushing-hands, and form.

Li Jin Fei: Tamo sword and tassel.

Han Jin Tang: chin na

Chih Ching Shih: Wu-T’ang sword fencing.

General Yang Shen (Disciple of Li Ching Yun): Taoist meditation.

Taoist Lui Pei Cheng: Taoist meditation and qigong.

Gordon Muir with Master Liang and Stuart Olson – 1985